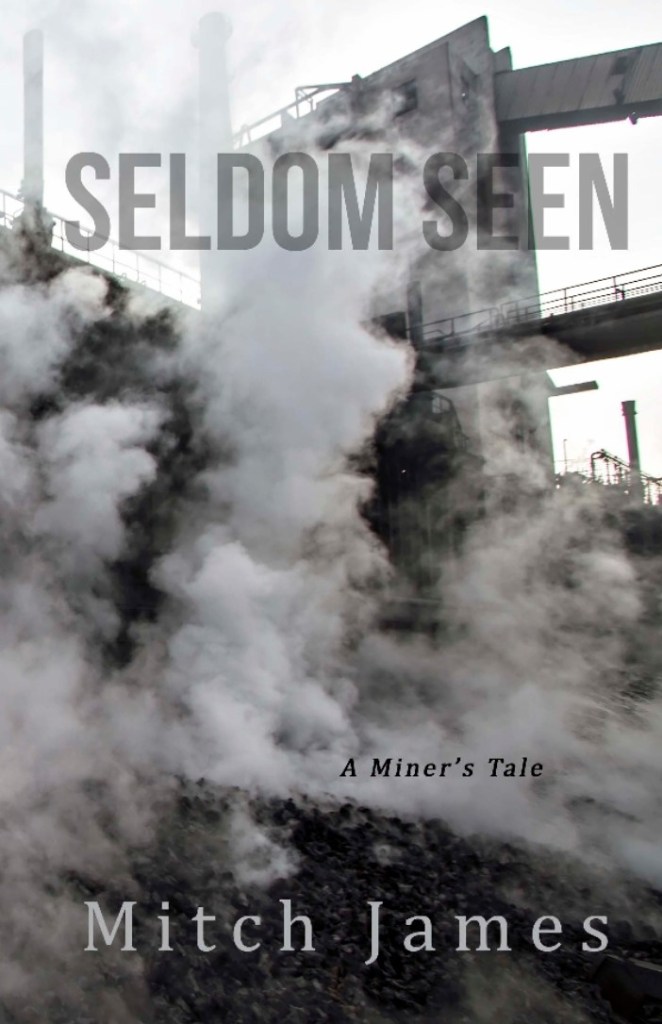

For my Appalachian lit aficionados, Grit Lit fans, and readers who aren’t afraid of the dark … I’m thrilled to share with you my conversation with author and professor Mitch James about his debut novel.

From the back cover, an intriguing blurb:

A dead mother. An auctioned childhood home. Loss in the womb of a coal mine.

Seldom Seen follows main character Brander, who encounters a “specter of a man who promises him that the answers to life are in Seldom Seen Mine, the largest coal mine in the United States.

With nothing holding him back, Brander … takes a job at Seldom Seen Mine, and fails at every attempt to amend his life, losing a friend, a lover, and maybe his mind.”

Reader friends, how does an author make good on such a blurb? I’ll tell you. With prose like this. I’m prefacing my first question for Mitch with one of my favorite passages in the novel. This is from early in the story, when Brander first enters Seldom Seen Mine:

Brander was surprised. The road was rather smooth and well-lit, the air stale but not dirty. They rolled along, everyone quiet. Brander stared around. The mine’s back had a skeletal structure of beams and crossbars and cribs, packed tight with backfill in places and all sealed up with gunite. It was surprisingly silent beneath the earth, the hum of the transport, the crunch of residue below the tires, the occasional whoosh of an air course. If not for the forced mechanization, there would be no sound, not like on the surface. Noise is life. But even free of men, the mine wasn’t dead, exactly; there was something, a kind of energy present in the long back road, an innate awareness, like the womb of a pulse-filled thing.

Mitch, welcome to Rust Belt Girl! Let’s dive in. The mine in this story works as much more than a compelling setting but a real character. I’d say we readers end up knowing as much about the mine as we do about Brander. How did you decide where to set this story? How did you learn so much about mines and mining? What kind of research did this entail?

I’m so happy to hear you’re engaging with the mine in that way because it is very much its own organism. It felt that way when writing the book, and it means a lot to hear that it felt that way to you as you read it. When I wrote the novel, I was up to my ears in rural Pennsylvania, working on farms, mountain biking old logging roads, kayaking rivers, and clearing land. I couldn’t get enough. I lived not far from the real Seldom Seen Mine. The research I did that allowed me to accidentally stumble into the idea for the novel also happened there. It was a perfect recipe—the need to express the region as I had experienced it as a transplant who had been there awhile, the need to tell Brander’s story, the need to imagine others’ lives and suffering alongside my own.

As for research, I read literary books on mining. There aren’t many. And I read short stories about mining in the U.S. and abroad. I read historical writing about mining at different periods in the U.S. in microfilm and microfiche. I watched a lot of YouTube videos, read instructional handbooks on mining equipment, found out who sold it, and found videos on how to operate it. I was friends with a mining engineer who guided me some. A little bit of everything.

Here at the Rust Belt Girl blog we’re a little fascinated with how place works in story. Place helps plots turn. Place also helps form characters. While a rural setting, I’d say that your Seldom Seen mine situates your novel squarely in Rust Belt lit territory. There are other commonly-appearing aspects to Rust Belt lit (or contemporary Grit Lit, writ large) that feature in your story: teenage pregnancy and the meth crisis for just two examples. Can you talk about how you explore such aspects of Rust Belt life and the characters living these lives without resorting to stereotypes in your novel (you do this well!)?

I’m relieved to hear you don’t think my characters are stereotypical. I would never want that. That said, though, if I’m being honest, I think all fiction runs off a little bit of stereotype. I think most readers need to see characters that are somewhat familiar and that present themselves as equations they believe they can calculate, at least at the start. Lucky’s the gruff, crude, masculine man. Brander is the wounded, self-loathing Midwesterner. But beneath the stereotypes that reveal a small percentage of what makes up who we are is the rest of us, the best of us, the parts of us that are unique. Brander and Lucky also have these qualities within them. It’s my job to complicate their stereotypes by fleshing out the rest of their characters, for they drive the story. I see stereotypes everywhere, including in myself. But by seeing them, I can perceive their limits, their boundaries; I can peer around them to what else presents itself, and that’s gold as a writer, the stories everyone tells but doesn’t mean to.

Basically, look for the people within the people and write about that. Then be prepared to conscientiously employ a little stereotype to get the ball rolling.

For those of us who are writers, ourselves, I wonder if you could take us through the process of crafting this novel. What was the first idea/image that came to you? When did you know you had to write this story? How long did it take? What’s your writing process like? We craft junkies want all the details!

The idea for the novel came to me when I was reading a translation of a Russian short story from the early 1800s, a story about a miner who encounters a ghost in a mine. The ghost starts manifesting in his life outside the mine until he goes insane and, if I remember correctly, kills himself. The story was so short. I wanted so much more. So I made it.

When did I know I had to write the story? Immediately. I can always tell the difference between something I could write and something I must write. I had to write Seldom Seen.

As for the process, I woke up at 3 a.m., wrote a 1000 words a day five or so days a week, and had the first draft in a few months. Then it took me 10 years to publish the book, so you can imagine the revisions, drinking, and self-loathing that occurred after repeated failures. Brander had to get it from somewhere!

I often wonder how Rust Belt lit will appear in American Literature textbooks a hundred years from now. Since you’re a college professor—maybe you wonder about this too? For me, my most formative American Literature course introduced me to William Dean Howells, the father of American realism. I’m not going to draw a perfectly straight line from American realism of the late 19th century to Southern Gothic of the early 20th century and the Grit Lit of today, but somebody could try. All that’s to ask where you see Seldom Seen fitting into the canon of American Literature? What are your reading/literary influences? What literary characters informed Brander, who—despite hard work and, yes, grit, fails, fails, and fails again?

It makes me feel a little pretentious to think of my work in any kind of canon. But my writing, including Seldom Seen, is influenced by myriad Appalachian, Midwestern, and American Western and South-Western writers, all rural and spread across the genres of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. I would hope Seldom Seenwould be welcomed by the Appalachian literary community and rural literary communities more broadly.

As for character influences, I have to be honest, I don’t know that I’ve ever consciously (though certainly subconsciously I have) created characters based on other characters about whom I’ve read. The characters begin with me, but they take over their story, and I just try and keep up and do justice through my writing to what they show me. I know that sounds mystic and woo-woo, but it’s the truth. For example, Lucky wasn’t a character I intended to have in the story, but when he showed up, he had plans, and I went along with them. Now, I can’t imagine the novel without him.

As for the last part of your questions, I don’t need to read a book to see hard work, grit, and abundant failure in a person. I’ve witnessed it in the working poor rural communities I’ve lived in my entire life. But I want to make something clear; I’m not saying the working poor are failures or that their efforts are in vain. I was working poor until I was thirty-two years old. I worked fifty hours a week with multi-billion-dollar industries and still had no healthcare or money, and couldn’t afford a vacation or a car that could make it out of the county. Goals like a home instead of a rental, good health insurance, the ability to take a vacation or have a safe vehicle all create comfort and stability in one’s life. The working poor are grinding but failing to reach important thresholds like these and others. There are many reasons why, but amongst them are certainly socio-economic and political barriers. These folks, my mother and father, cousins, aunts, uncles, neighbors—they’ve taught me how to create characters with grit that fight and fight and fight.

This world has shown me how to write characters who fail.

And final question: What are you teaching, reading, and writing right now? What’s next?

I’m teaching various writing composition courses. I’m reading, gosh, so many random things. I feel like I read and read and finish nothing. I’m reading Larry McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By; Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead; Adam Grims’ The Art and Science of Technical Analysis; Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart, and a textbook on world history because I screwed around too much in school when I was younger. I’m ashamed by how much basic knowledge I missed out on for being too stupid to know better.

As far as writing goes, I just finished a book of poetry that a press requested and for which there is a promising chance of publication. I’m pitching a couple of short story collections and two novels and am kind of tinkering around on a new one, so if there are any publishers/agents out there who think my work and I might be a good fit, reach out. I’m doing some final revisions on two peer-reviewed articles due out soon as well. Keeping busy.

Upcoming? I’m excited about the Lit Youngstown Fall Literary Festival. It’s one of my favorite events all year!

Mitch James is a Professor of Composition and Literature at Lakeland Community College in Kirtland, OH and the Editor-at-Large at Great Lakes Review. Mitch is the author of the novel Seldom Seen: A Miner’s Tale (Sunbury Press) and has published works across the genres of short fiction, poetry, and academic scholarship. You can find his latest short fiction in Made of Rust and Glass: Midwest Literary Fiction Vol. 2, Red Branch Review, and Bull; poetry at Shelia-Na-Gig, Watershed Journal, I Thought I Heard a Cardinal Sing: Ohio’s Appalachian Voices; and scholarship at Journal of Creative Writing Studies. Find more at mitchjamesauthor.com and on Twitter @mrjames5527.

Like this interview? Comment below or on my FB page. And please share with your friends and social network.

Check out my categories above for more interviews, book reviews, literary musings, and writing advice we can all use. Never miss a post when you follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~Rebecca