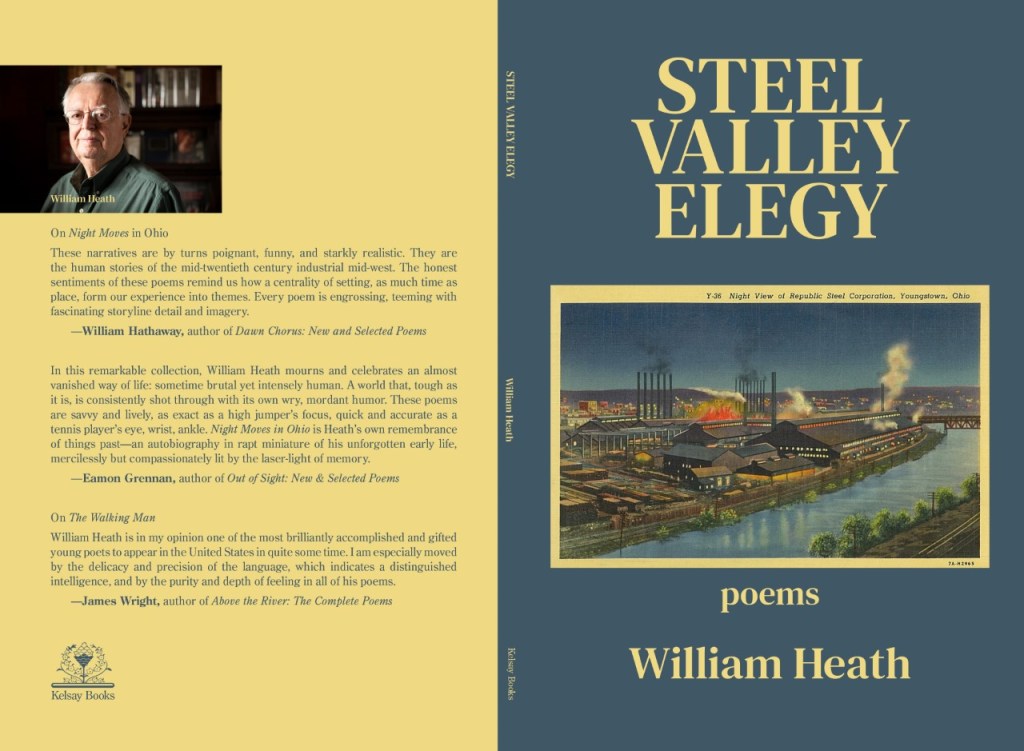

William Heath, born in Youngstown, grew up in the nearby town of Poland. A graduate of Hiram College, he has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Case Western Reserve University and has taught American literature and creative writing at Kenyon, Transylvania, Vassar, the University of Seville, and Mt. St. Mary’s University, where the William Heath Award is given annually to the best student writer. He has published four poetry books: The Walking Man, Steel Valley Elegy, Going Places, and Alms for Oblivion; three chapbooks: Night Moves in Ohio, Leaving Seville, and Inventing the Americas; three novels: The Children Bob Moses Led (winner of the Hackney Award), Devil Dancer, and Blacksnake’s Path; a work of history, William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest (winner of two Spur Awards and the Oliver Hazard Perry Award); and a collection of interviews, Conversations with Robert Stone. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Hiram. He and his wife Roser live in Annapolis, Maryland.

Let’s begin with a taste of “Steel Valley Elegy” from William Heath’s poetry collection of the same name. Here’s the first stanza:

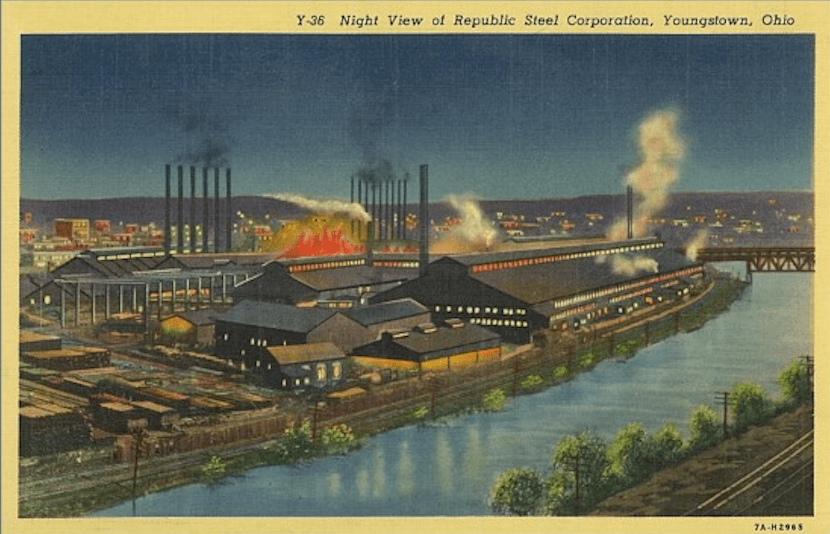

I speak Steel Valley American. Once mills

lined the Mahoning River from Youngstown

Sheet and Tube’s Jeannette Blast Furnace

on Brier Hill to Republic Steel in Struthers.

Coal intensified to coke turned iron ore

into molten ingots that were rolled into slabs,

scarfed free of impurities, shaped for strength:

bridges to span waters, girders for skyscrapers,

tanks, ships, guns, and shells to win World War II,

machines and factories for our bounty.

What I love about this poem is how the poet unearths the beauty (and more obvious power and destruction) present in industry, a beauty borne by the transformation of a thing, like dirty coal, to another thing, like shining steel.

The transformation is accomplished by people and fire, which always lends to these scenes of the mills a sense of the miraculous for me, something to be found among the gods of Olympus. And if I spin out this analogy, steelworkers are mini gods then, prone to falling from on high, of course—so much transformation and story in this history of our shared native place.

William, you are from one of my favorite adopted cities, Youngstown, Ohio (“Little Chicago,” as you call it in the above poem). Can you tell us about your Rust Belt upbringing and how it perhaps sparked your creative work? Or has informed it? Did you dream of becoming a writer and teacher when you were young? How did place factor into those dreams?

I was born in Youngstown in 1942, spent my first six years in Gerard. I have few memories of that other than a big snow that we kids tunneled under and riding a neighbor’s large dog. My parents, Oberlin graduates, were teachers; my dad became principal at Hays Junior High in Youngstown; my mom substituted a lot in a variety of subjects. The family moved to Poland, a small New England style town nearby where my memories begin. Like most boys I was interested in sports and girls, not necessarily in that order; the poems that start off Steel Valley Elegy are based on my boyhood. For better or worse, I was better at sports than girls, especially basketball and track. Poland High won the sectional tournament, which meant beating the best Youngstown teams, then lost to Warren in the next round (I was guarded by the future Ohio State and Cleveland Browns star Paul Warfield). In track I qualified in the high jump for the state tournament in Columbus, where I was an also-ran against that top competition (no small school/large school divisions then).

When I was a boy I wanted be a high school history teacher and a basketball coach, then at Hiram College I widened my perspectives: switched from Republican to Democrat, decided to become an English professor. Since teenage boys love to brag, what was most notorious about my area were Mafia wars to control a gambling game called “the bug,” resulting in many bombings, at least a dozen deaths; Youngstown was dubbed “Little Chicago.” I never witnessed first-hand any of that violence, but when I was visiting my cousin in posh Shaker Heights, I saw the aftermath of a shooting described in “A Hit in Shaker Heights.” I once was a suspect in a robbery at a boathouse where I worked in the summers that brought me to the dreaded Youngstown police station for a lie-detector test, see “An Inside Job.” In sum, I lived a fairly typical small town Midwest boyhood, with the usual teenage antics that feature in some of my poems, while next door was a thriving steel city with a lot of good-paying union jobs but also a gangland war between the Cleveland and Pittsburgh mobs.

Your literary influences are many. With a Ph.D. in American studies, you became a professor, poet, and novelist. Your 1995 novel, The Children Bob Moses Led, is about the civil rights moment in Mississippi. Mississippi is fairly far afield from your Ohio beginnings. Can you talk about the inspiration for this historical novel?

After majoring in history with a minor in English at Hiram, I went to Case Western Reserve University in American Studies. As a college teacher, I realized my students knew little about the civil rights movement. I began my writing career as a poet, then switched to writing fiction, and decided to write a novel about Freedom Summer in 1964, when college students, mostly white, went to Mississippi where three young men were murdered by the Klan shortly after they arrived. That courageous effort was a moral high water mark of my generation, and I wanted to write a true account of it. Bob Moses (a charismatic Black man from Harlem who had studied philosophy as a graduate student at Harvard) was the key SNCC leader, indeed he was a legend in the movement; he died a few years ago and lamentably is largely forgotten. I had participated in the March on Washington in 1963, not Freedom Summer; I knew about the civil rights movement but not nearly enough. I devoted many years of research to the project, my most important archives were the SNCC papers at the Martin Luther King Center in Atlanta and the invaluable Sixties files at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. My wife and I made several trips to Mississippi where I interviewed Black and white participants in Freedom Summer. I have a wealth of stories about those experiences, one is recounted in Alms for Oblivion, “Preacher Knox.” Several of my other poems about the South appeared in The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, my favorite name for a poetry magazine.

I like to think that my skills as a novelist, historian, literary critic, and poet enrich each genre.

The Children Bob Moses Led was published by Milkweed Editions who made it their feature fall selection and nominated it for the Pulitzer Prize. It did win the Hackney Award for best novel, was reissued as a paperback, and then re-printed by NewSouth Books (now a part of the University of Georgia Press) in a twentieth-anniversary edition. It has sold the most of my novels and has been used in classes from junior high to graduate studies. My multi-award winning history book, William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest, has also sold well and remains in print. Both books epitomize my interest in American Studies, since I was able to draw upon my extensive interdisciplinary training to cover multiple aspects of the topic to make them valid history and vivid literature. I think my early years as a poet also served to give my prose a distinctive tone. I like to think that my skills as a novelist, historian, literary critic, and poet enrich each genre.

You began publishing your poetry in the 60s. Can you talk about the differences between writing the novel and writing poetry? Have you found that there are seasons of life for each, when you are drawn to one form or the other? Or is it that the subject matter demands the form? Can you talk a little about your creative intuition or your creative process, or both?

My first teaching job was at Kenyon College, then the epicenter of contemporary writing thanks to John Crowe Ransom’s Kenyon Review, which drew a host of talented students and teachers to that lovely campus in rural Ohio. I attended his 80th birthday party and met several famous authors, including Robert Lowell, Kenneth Burke, Peter Taylor, et. al. Carl Thayler, an older student who had been a bit player in Hollywood films and was intensely interested in poetry, also brought writers to the campus—that is how I met Toby Olson and Paul Blackburn, who encouraged me to write. For the first fifteen years of my college teaching career I wrote mainly poetry and published some hundred poems in various little magazines, but that did not carry much weight when I came up for new contracts and tenure. Thus I went from Kenyon, to Transylvania (where my poetry writing improved markedly), to Vassar; in 1979 I was selected as a Fulbright professor of American literature at the University of Seville.

During phase one of my poetry career, I was influenced by William Carlos Williams, James Wright, Philip Levine, as well as other poets who wrote free verse with a sharp-eyed realism about the gritty side of American life. I was drawn to the idea that poets should be grounded in specific images that evoke the world of the poem and resonate with readers. I read poetry widely in those days and had strong opinions about many poets. At some point, however, I made a major mistake: I decided that the next poem I wrote should be better than the previous one; not surprisingly that proved counterproductive. I also was frustrated that my focus on poetry stood in the way of obtaining a permanent place in my profession. At Vassar, I solicited comments from contemporary poets I admired, but did not know personally; as a result I received high praise from James Wright, Philip Levine, Richard Wilbur, and others that was certainly encouraging, although their kind words did not move the tenure committee at Vassar.

More than one critic has noted your adept storytelling in your poetry. Do you come to a poem with a story in mind you’d like to tell? Or do you usually begin with an image and a story emerges from it? Can you point to a poem of yours I haven’t mentioned here that tells a particularly necessary or good story?

I like to tell stories, covering a wide range of topics; I think that is one of my strengths. My first poetry book, containing the best of my early work, The Walking Man, opens with “The Boy Who Would Be Perfect,” a true story based on a summer I spent as a counselor at a camp in the Adirondacks teaching boys from wealthy Jewish families in Great Neck, Long Island, how to play tennis. As it turned out, two of ten boys in my cabin were mentally disturbed, something I had not been told; they proved to be very difficult. I conflate the two boys into one in the poem, which is true to what transpired. That summer I also took my campers at night to see black bears (they didn’t believe bears existed anywhere near them) feeding at a garbage dump—but that’s another story yet to become a poem.

When I returned to writing poetry following my retirement in 2007, I realized that many of the stories I liked to tell had poetic possibilities—a particular focus and sharp images—so I turned them into poems. Steel Valley Elegy opens with autobiographical poems that tell stories; my next book, Going Places, features stories about the two years I lived in Seville, the next section contains poems based on the years (when you add up all the extended visits) I spent in or near Barcelona, where my wife was born. My most recent book, Alms for Oblivion, has narrative poems, a few several pages long. Some narrative poems are not from personal experience, rather on the experiences of my generation, such as “Chicago 1968,” “Bringing the War Home,” “Shut It Down,” “At the Commune,” and “Jail, No Bail.” As with The Children Bob Moses Led, they are designed to put the Sixties into critical perspective.

Your most recent poetry collection, Alms for Oblivion, is broken into six parts. Part II is titled Flyover Country. The poem by the same name concludes: “We folks down below look up / and out … Beware of our resentment.”

Reading that poem, of course the notion of “flyover journalism” comes to mind, when a place’s stories are told by outsiders. As I am like you, a NE Ohio native living on the East Coast, I’m wondering, how do you keep at least somewhat rooted to your native region in your work? Through memory and history? Do you return to Ohio? Are there literary organizations, local news outlets, or podcasts you seek out for a current, local perspective?

What is your relationship now to the notion of Flyover Country, and why do you think it keeps popping up in your work, despite having lived on the East Coast for many years now?

As you note, “Flyover Country” tries to capture how people in the Midwest feel about the rest of the nation looking down their noses at them. This is not always true, but has become an article of faith; the resulting “resentment” helped lead to the disastrous, in my view, reelection of Donald Trump, who has no interest in or understanding of the Midwest but an uncanny ability to play upon people’s fears and anxieties. My parents have been dead for years, but my sister still lives in Delaware, Ohio, and I visit her every year or so. I have attended the Buckeye Book Fair in Wooster, the Midwest Historians Convention in Grand Rapids, the Youngstown Lit festival, and the Ohioana Book Festival in Columbus. That enables me to keep in touch with what is happening on the ground in Ohio and elsewhere (I also lived in Kentucky for five years). I must admit I am delighted to do a Rust Belt Girl interview, because like you I love the Midwest (even if I sometimes weep for it).

For better or worse I am not a high tech person; my cell phone stays in my car, I respond to Facebook posts but rarely post myself; I’m on Linkedin but never use it; I have never twittered; when asked for my twitter name I sometimes respond “Curmudgeon.” This dates me, I know, yet I really would welcome poetry lovers who are active on the internet, if they are so inclined, to promote my work. I would love to see one of my poems go viral! George Bilgere, a poet we both admire, did include “The Vet” on his wonderful Poetry Town recently. And Grace Cavalieri featured me on her “The Poet and the Poem” series from the Library of Congress.

Before you lived in Maryland, you and your wife, the novelist Roser Caminals-Heath, lived in Europe and traveled extensively. While remaining rooted to your past, your poetry takes the reader to foreign shores, as it were. “The Starlings of Rome” is one I particularly like. Here are the first few lines:

At setting sun hundreds of thousands

swoop and swarm over the Vatican

and other vital organs of the city.

What I notice in these lines is a simplicity and a precision in the language and—and I might be reaching—a return to the body. We’re talking about starlings making their ethereal patterns in the sky; yet “organs” brings us back to ourselves, back to earth then. Do you see it this way? I’d love to know how you developed your poetic style that is at once reaching and reachable, if that makes sense.

I’m grateful you asked about my wife Roser, who as you mention is a distinguished writer in her native Barcelona. She writes in Catalan, a distinct language from Spanish, and has published ten highly praised novels, one won the prestigious Saint Joan prize. Steel Valley Elegy contains poems set in the United States, while its companion volume, Going Places, is set abroad. I met Roser when I was a Fulbright in Seville and she was at the University of Barcelona. For years we spent our summers at Vilanova i la Geltru on the coast, then her parents moved to Frederick, MD until their deaths. We love to travel, not only in Catalonia, which Roser considers a separate country from Spain, but extensively in Europe and elsewhere, including Russia, Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Canada, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Mexico. Our most exotic trip was to Nuku Hiva, in the Marquesan Islands, for a Melville conference. A few poems in Going Places are set in countries I have not visited in person, only in my imagination. Especially in my poems set in Spain and Catalonia, I try to speak not like a tourist and more like someone with personal knowledge of a people and place.

As you mention concerning “The Starlings of Rome,” my poems are based on concrete images and thus have “body.” The starlings make marvelous spirals in the sky, suggesting a spiritual dimension, while their droppings present a major problem. It’s that double-sided nature of life that appeals to me. The “Starlings” poem is part of a sequence detailing how strangely other creatures sense the world with its good and bad vibrations. Wallace Stevens once said “the greatest poverty is not to live in the physical world,” and William Carlos Williams added “No ideas / but in things.” Hence the human body and the “body” of the world are essential to me in poetry, which should draw on all of our senses—taste, touch, sight, hearing, smell. In my fiction, I also ground my work in a lot of physical detail, “How the weather was,” as Hemingway once said. Hence I keep my characters in fiction, and the speakers in my poems, in voice, each with a distinctive way of saying things.

With eco-fiction booming and nature poetry always compelling, I read with interest “The World at Low Tide,” which feels like a nature poem and cautionary tale all at once. Here’s the first stanza:

High above spruce trees

the rosy breast of a soaring gull

catches the glory of the risen sun.

Seabirds skim over tide flats

waiting to feed on what waves

bring in and leave behind.

Can you talk about the inspiration for this poem or other nature poems of yours? Does living on the crowded coast put into stark relief our relationship to the water and earth we call home? How does this place infuse your poetry?

Although I’m from the landlocked Midwest, I am very fond of coastal settings, especially the Mediterranean but also here in Annapolis on the Chesapeake Bay where we have lived since 2022. Every summer we go to Lewes, Delaware, for a week at the beach; and in the winter to Key West (I have written poems about both places). As Melville wrote, “meditation and water are wedded forever,” which also brings to mind a haunting Robert Frost stanza:

They cannot look out far

They cannot look in deep

But when was that ever a bar

To any watch they keep.

These lines capture the poignant, sometimes troubling, limited nature of us human beings. I must admit the lines are more troubling nowadays, since Trump’s re-election. I had hoped for more from my fellow citizens than they were able to give. As I say in one of my yet to be published poems on the election: “we are not / who we think we are / or pretend to be.”

Coastal areas do draw out a meditative dimension in us, I think, we gain a deep sense of time since we know the ocean and its waves have been doing the same thing for eons, and will continue to do so. Not much seems to change in the short term, but in the long run we know that continents shift position, species come and go, and thanks to climate change and human limitations, our species may not be around as long as we like to assume it will. I try to write poems that capture something of the processes that surround us: how do I love thee / let me count the waves, as the poet might have said.

As a professor for many years, what poem did you most love to teach—of your own, of another poet, either historical or contemporary? And why?

When I taught poets I admired like Whitman, Dickinson, Williams, Stevens, Frost, et. al., I used to look first for short poems—I call them “program poems”—that suggest what the poet’s sensibility and assumptions are. Williams’ “The Red Wheelbarrow” poem, for example, is by no stretch a major poem, yet it is a concise introduction to what he is up to in terms of images; then I would move on to poems I did consider major like “To Else,” the one that begins “beat hell out of it / beautiful thing.” A favorite statement about what makes a poem good poetry is by C. S. Lewis, which goes something like “To Write a great love poem, you may or may not have been greatly in love, but you must love language.” “On Poetry,” in Alms for Oblivion, is one of my attempts to say what poets should aim for. I would place my own poems in a tradition that goes back to Catullus, whose blunt, often obscene poems broke through social and poetic decorum to strike us with an irrepressibly lively human voice. Another favorite, by the way, is Keats’ “What shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon poet.” While opinions will always differ, I do believe that some poems are much better than others, and I made an effort to teach poems I thought were a poet’s best (I often disagree with those selected for anthologies). As a poet I use the analogy of baseball: a single is a poem, a double is a good poem, a triple is a very good poem, and a homerun is, well, a homerun. The more students are taught to appreciate those “homeruns” the better. Value judgments are relative, but they not absolutely relative.

I’m enthralled by creative couples. How do you and your wife inform each other’s work or creative life?

Contrary to popular belief about literary couples, my wife and I are not jealous of each other’s work and we see ourselves as co-conspirators in our life and our writing. Unfortunately, because I know very little Catalan, I can offer her no help with her prose, although I do serve as a sounding board for her ideas as a novel is in progress. I hope that I am of help in that way. Roser, on the other hand, is of enormous help to me. She reads drafts of all my work. I try to give her what I consider a polished draft—when it returns from her red pen I realize how wrong I was—and this serves as a welcome stimulus to try harder, as revision follows revision. I believe that the best poetry and fiction are written in a kind of reverie, producing rough drafts that must then be revised with lucidity. Vladimir Nabokov used the analogy that his pencils outlive his erasures. Everything I write is revised numerous times, a process I find very satisfying, since I always feel even the smallest changes make a manuscript better. I am astonished and appalled by the notion that all works of literature are created equal and value judgments are of no value. Why would any author strive so hard to write as well as possible if that were the case? When I wrote fiction, Roser often accompanied me on my research trips, some quite memorable like our various visits to Mississippi—Indiana, not so much—and I always enjoy going with her to Barcelona for her media interviews and other PR events related to the publication of one of her novels.

What are you reading and writing right now?

When I retired in 2007 to devote myself to writing, the first ten years of that resulted in a novel, Devil Dancer, begun during my Fulbright years in Spain then revised multiple times before coming out as a book. During the decade I also published a historical novel, Blacksnake’s Path: The True Adventures of William Wells, and a history of his life, William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest (University of Oklahoma, 2015), which won two Spur Awards from the Western Writers of America and the Oliver Hazard Perry Award for military history. It is still available in paperback and sells well at book fairs and my talks at history centers. I didn’t devote myself fully to writing poetry again until 2017. Since then I have published some 350 poems and three full-length poetry books plus three chapbooks.

My next poetry book, Not My Country, will open with poems about the dangers Donald Trump presents to our democracy. While I think my poems stand out for my distinctive voice, the way I move a poem down the page, and the wide range of topics I dramatize, I believe poets are obligated to reflect what’s happening around them. The re-election of a person who is literally insane, with an acute case of malignant narcissism, presents a daunting challenge for our country that must be addressed; I plan a series of viable poems that depict the situation. Other sections of the book will deal with my usual topics: autobiography, meditations, Americana, travels abroad, and so forth. Some titles already published that will appear in my next book suggest that most of my poems won’t be about our dire political situation: “Killer Whales Attack Yachts Off Gibraltar,” “Trigger Warnings,” “Men’s Book Club,” “Walt and the Supremes,” “Prime Time,” “Bass Man,” “A Trip to Montreal,” and “Big Man on Campus.”

Since I’ve returned to writing poetry full time, my reading habits have changed. In my first incarnation as a poet I read as many poets as I could to find out whom to admire and emulate while keeping my own signature. I wrote a short poem about the process: “read a lot of poetry / until it starts / coming out your ears / then listen.” During the decades I was mainly a novelist, historian, and literary critic, my reading was in those genres, while now I read mostly poetry and books that I think might stimulate my poetic imagination. A good example of the latter is Ed Yong’s An Immense World, which inspired me to write a sequence of nature poems that appear in Alms for Oblivion. Some of the poets I’m reading nowadays are old friends, David Salner, Holly Bergon, Hope Maxwell Snyder, and Kit Hathaway, as well as new discoveries like George Bilgere, Bob Hicok, and David Stevenson. I also make good use of my extensive library that contains the selected or collected poems of many important poets.

I always keep in mind the words of William Carlos Williams that “it is difficult to get / the news from poems,” as well as his lines addressed to an old woman: “I wanted to write a poem / that you could understand / for what good is it to me / if you can’t understand it?” Most people are baffled by poetry, and go into a sort of panic mode when presented with poems to read. My poems are not “obscure,” I write in the American idiom in lines that are concise, direct, and clear. My poems often, as we noted, tell stories, and their images speak to each other, providing coherence and resonance. This year I once again will be working to open my imagination to new poems and trying to find the best words to bring them to life.

For more info, see www.williamheathbooks.com

Signed copies of William Heath’s books can be at Bill’s Books, a part of abebooks.com.

Like this interview? Comment below or on my fb page. And please share with your friends and social network. Want more? Follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~ Rebecca

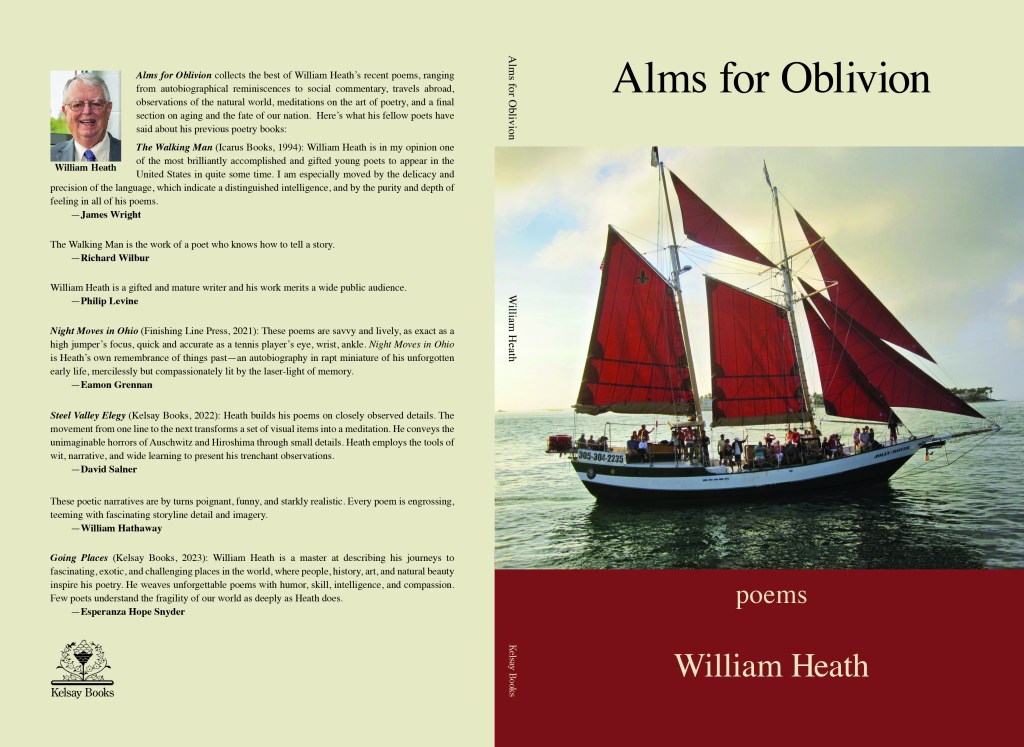

*Images provided by William Heath