A guest post by John W. Miller

The genesis of the PBS film Moundsville and its companion blog Moundsville.org, about a classic American postindustrial town, was a mid-life crisis mixed with the 2016 election and a curiosity about the truth of Rust Belt communities.

Six years ago, I was on staff at the Wall Street Journal, covering mining and the steel industry out of its Pittsburgh bureau.

Like everybody else, I watched as the Trump-Clinton presidential election blew anger, confusion, and fear through the culture.

Personally, I was going through my own crisis. I was about to turn 40, and experiencing mid-life’s deepening cravings for meaning and direction. That second mountain beckoned.

After 13 years roaming the world for one of the world’s great newspapers, I simply wasn’t enjoying it anymore. So I quit, and started climbing. After some discernment, I decided to stay in Pittsburgh.

Poking around for creative projects, I started driving to Moundsville, a small town in West Virginia on the Ohio River 75 minutes from Pittsburgh. In 2013, I’d reported on it for the Journal.

The town fascinated me. I grew up in Belgium, the child of American musicians who’d wandered around Europe in 1976 and dropped an anchor in Brussels. I’m fascinated by places in America that tell a deeper story about my ancestral homeland.

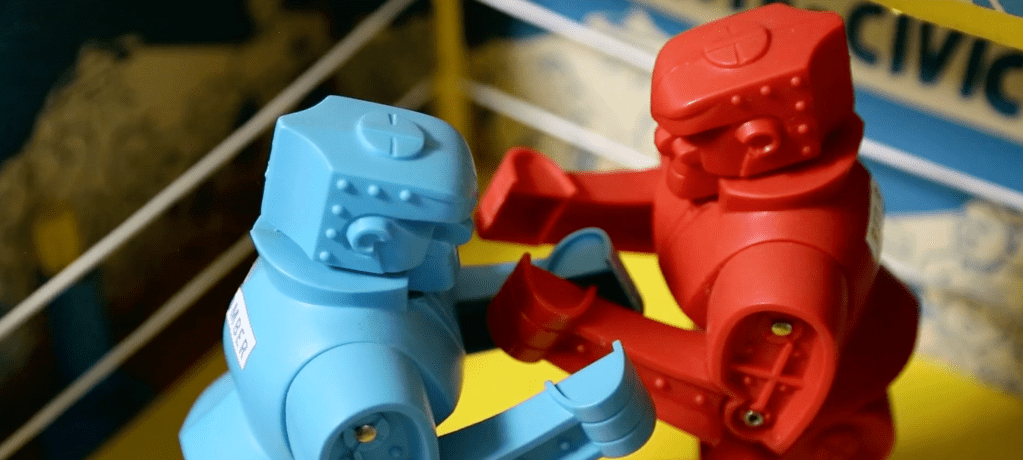

In late 2017, I connected with filmmaker Dave Bernabo. We put together a proposal to tell the story of Moundsville in a documentary. I thought that town was a perfect place to tell a deeper story about America because it’s built around a 2,200-year old Native American burial mound, it harbored a glorious industrial age including the world’s biggest toy factory (Marx Toys, maker of Rock’em Sock’em Robots!), and it now subsists on a service-based economy anchored by a Walmart. There’s also a lot of pain and grief in Moundsville. In a generation, the town lost 8,000 jobs. The population halved. Young people left for Pittsburgh and New York.

David and I spent most of 2018 driving down to Moundsville and interviewing people. At the end of each interview, we’d ask a question about Trump and national politics. Almost always, the answers lacked depth. It dawned on me: These people didn’t know about Trump. They didn’t live in DC. They weren’t very thoughtful about politics. But when we asked them about their work lives and their parents’ work lives, they engaged with depth and wisdom. Those questions, I realized, were actually loving. Almost always, I decided, asking about Trump simply wasn’t loving.

After experimenting with a voiceover, we opted to tell the story without a so-called “voice of God” as narrator. The movie is an oral history, without any academics or outside experts.

In our interviews, we heard about grief a lot, but we also heard and told tales of resilience, from a back-to-the-land farming couple, a small manufacturer of kitchen cabinets, and the leaders of a burgeoning tourism sector. The ancient burial mound looming above the town is a daily reminder that civilizations ebb and flow, and that time moves only forward. My hope is that we acknowledged grief in a healing way while pointing the way forward with stories of hope and perseverance.

In December 2018, we premiered Moundsville in the town itself, a practice of sharing work that anthropologists recommend. Over 170 people showed up. A few grumbled about our portrayal of segregation in the film, but at the end, we received an ovation.

A month later, we screened at America, the Jesuit magazine I had started writing for, in New York City, on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan across the street from News Corp., home of the Wall Street Journal.

To my surprise–and gratitude–the movie holds up. People appreciate its openness and listening attitude. “This amazing project reflects a diversity of stories that I needed to experience to remind me of hope and resilience and kindness,” wrote Anupama Jain, head of a Pittsburgh diversity training group, on Twitter.

The biggest lesson I’ve learned making and showing Moundsville is that every place carries an organic placeness that deserves respect for its uniqueness. You can find wisdom and thoughtfulness in people when you engage them over that place and recognize its differences from your place. We can’t love our neighbors as brothers and sisters if we expect them to be just like us.

I created the Moundsville.org site to promote the film, but quickly found an audience for pieces I was posting. It gets an average of 10,000 readers a month. So I keep writing and posting. I’ve written over 100 pieces for the blog, on everything from Lady Gaga’s mom, who grew up in Moundsville, to people going to watch baseball inside the prison in the 1950s.

I’m still on a journey of figuring out a new kind of journalism that suits my skills, and my heart. I’ve co-directed Out of Reach, a new movie about the American Dream. I’m developing a podcast called Philosophy with Strangers, where I go with an older friend to small towns and ask big questions. First episode: We went to Charleroi, PA and asked people: What is happiness? I contribute regularly to America, a monthly magazine run by Jesuits. I coach baseball. Lots of other stuff, too. But wherever my career takes me, it was forever changed by the road that ran through Moundsville, West Virginia.

John W. Miller is a Pittsburgh-based writer and filmmaker, and co-director of the PBS film Moundsville.

~~~

What are you watching, reading, and writing this month. Let me know in the comments…

Are you a Rust Belt writer? What’s your story? Would you care to share? Do you write book reviews–or conduct interviews of Rust Belt authors? If so, think of Rust Belt Girl for a guest post. And check out the handy categories for more writing from rusty places.

Find me on FB and on IG and Twitter @MoonRuark

And follow me here. Thanks!