I’m thrilled to share this guest post interview with Rust Belt Girl readers. What began as a Spotlight interview–between two of my favorite authors and people–for the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) has been gifted to us here, and I’m so grateful.

We talk a lot about writing as a communal act at Rust Belt Girl and about finding that community where we belong. The first time I met Karen Schubert in person, I’d just driven five hours, home to Ohio, to attend a literary festival I’d never been to before. I knew a few names but no faces. And no one knew me, so I dutifully popped on my name tag.

Even before my nerves could kick in, here comes the director, Karen Schubert, with the most gracious greeting–as if I were the keynote or a fully-fledged author, and not an emerging writer and editor with a blog.

I belonged. Just like that. And I’ve returned to that annual literary festival every year since. Last year, I served on the planning committee to do my own small part in welcoming new faces to the community.

“How does she do it?” This is a question I often ask about Karen Schubert. In addition to being co-founding director of Lit Youngstown, a literary arts nonprofit with programs for writers, readers, and storytellers…

Karen Schubert is the author of The Compost Reader (Accents Publishing), Dear Youngstown (Night Ballet Press), Black Sand Beach and Bring Down the Sky (Kattywompus Press), I Left My Wings on a Chair, a Wick Poetry Center chapbook winner (Kent State Press), and The Geography of Lost Houses (Pudding House Publications). Her poems, fiction, creative nonfiction, essays, reviews and interviews have appeared in numerous publications including National Poetry Review, Diode Poetry Journal, Water~Stone Review, AGNI Online, Aeolian Harp, Best American Poetry blog and American Literary Review. Her awards include the William Dickey Memorial Broadside Award, an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award in poetry, and residencies at Headlands Center for the Arts and the Vermont Studio Center. She holds an MFA from the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts.

Thank you to Robert Miltner for asking “How does she do it?” here and to Karen Schubert for telling her story–and inviting us to tell ours.

Robert Miltner: Karen, you live in Youngstown, a midwestern rust belt city located within the Appalachian Ohio region. Your city was known for its blast furnaces and mills that, as Bruce Springsteen sings in “Youngstown,” “built the tanks and bombs that won this country’s wars.” In your poem, “Letter to Youngstown,” you write “Remember the world is full /of places like Youngstown, /and places nothing like Youngstown.” How does that reflect your sense of identity as the director of Lit Youngstown?

Karen Schubert: I’m not from here, although my mother’s family has been in the area since the early 1800s. I came to live in my grandparents’ farmhouse that I loved visiting as a child, and now I live in the city, in a five bedroom brick and frame house that must have been a stunner with its slate roof and cedar shakes. I bought the house on a teaching adjunct’s salary; that tells you what’s going on here. I think there’s a benefit in having been other places and having a sense of how things might work. But I’ve also been in Youngstown long enough to know what people might miss or seek, what our assets are, and who is doing amazing work. I once attended an AWP session on starting a literary arts nonprofit and someone said, “I can’t convince anyone to get behind what I’m doing because they don’t understand the concept.” I thought, that’s a problem I’ll never have.

Youngstown is economically poor yet arts rich…

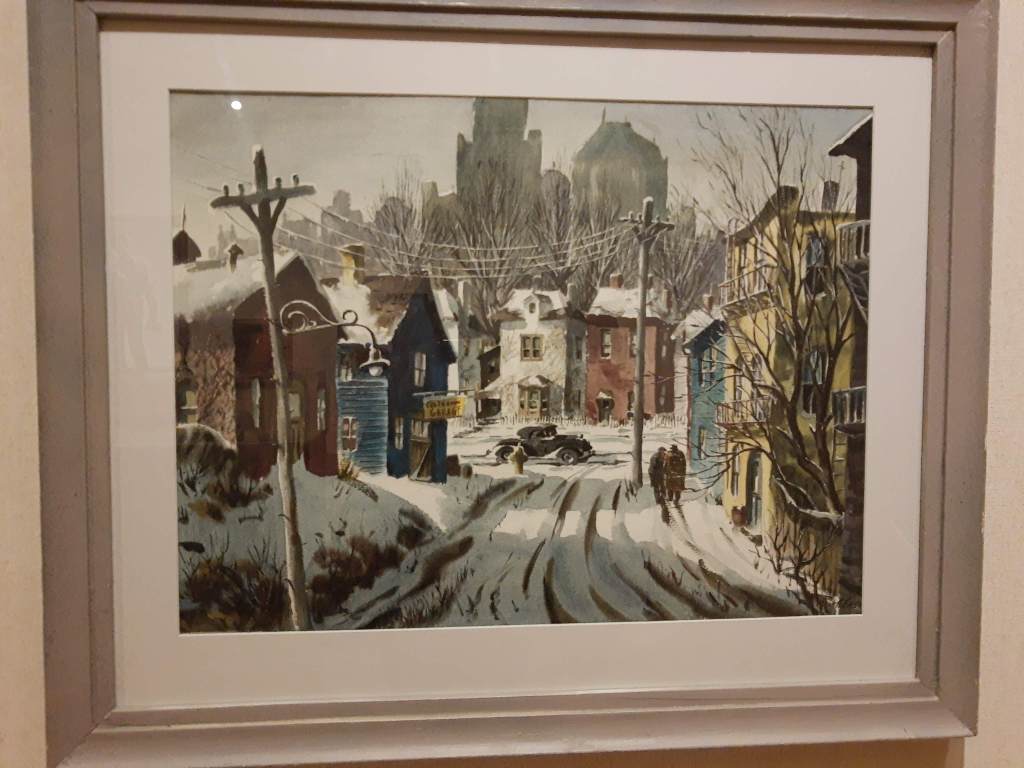

Youngstown is economically poor yet arts rich—live music, performing arts—with an opera and two extraordinary concert halls including the original Warner Brothers theater, and several local theater companies. The visual arts are available through an outstanding American arts museum and a university museum. On the river, the shell of a steel mill came down a few years ago and a new amphitheater went up. In recent years, the city has hosted Margaret Atwood, Gloria Steinem, and Tarana Burke, as well as YoYo Ma through Kennedy Center outreach. Youngstown is also rich in literary arts. Lit Youngstown hosts readings at a supportive for-profit art gallery that champions local artists. While many community-based writers and writing program faculty stayed and enrich the community, like Christopher Barzak, Steven Reese, Will Greenway, and Philip Brady, others have left to great success, like Ross Gay, Ama Codjoe, Allison Pitinii Davis, and Rochelle Hurt. There is also a local culture that benefits from the immigrant grandparents who taught their children a profound love for the arts.

Youngstown State has been a part of the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts [NEOMFA]; in fact, it was founded at YSU, and we were devastated to learn that YSU has decided to sunset their participation in the consortium. We are still processing the loss that will be to Lit Youngstown and the community.

Miltner: What inspired you to start Lit Youngstown in 2015?

Schubert: I lived in Cleveland for a few years, and there were many literary gigs. The summer of 2013 I was a writer-in-residence at Headlands Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and talked to writers and artists all summer who were doing fascinating work. I began wondering what might be possible in Youngstown.

Miltner: Did your experience as an AmeriCorps VISTA at a neighborhood development nonprofit influence your decision to start Lit Youngstown?

Schubert: Yes, certainly. I was hired by Youngstown Neighborhood Development Corporation to write for the Neighborhood Conditions Report including data from every census tract in the City. Grim statistics: 40% of city land abandoned, jobs clustered in edge suburbs, and Black infant mortality rates similar to Guatemala. But I also learned that incredible things were happening, important stories that needed to be told. One day we were out interviewing residents and a woman invited us inside. She was a member of a Black women’s motorcycle club. They had filled a dining room with long tables, conveyor-belt style, and were packing stacks of to-go boxes with dinners for local residents who were struggling. This is an example of Youngstown’s story, its resilience and social weave. What I learned from the neighborhood development nonprofit is to be fearless: work hard, collaborate, research, and don’t buy the idea of staying just in your lane, because everything is connected.

Miltner: How wide an array of literary programing does Lit Youngstown offer?

Schubert: We host a monthly reading series, writers critique group, book and film discussions, writing classes, a Winter Writing Camp for all ages, teen writers workshops, and a Fall Literary Festival. We also do many one-off events and collaborations, including an NEA Big Read grant with the public library and reading lunch poems with adults with disabilities at the nonprofit Purple Cat. One of our early projects was Phenomenal Women: Twelve Youngstown Stories. We interviewed Black women between the ages of 64 and 101 and published their stories and images from their lives. The collection is a rich archive of our city’s history, and the idiosyncratic details of the lives of these tremendously strong, intrepid and insightful women. One of the women worked in the War Room during the FDR administration. Many were tapped for jobs during the Civil Rights movement, to hold newly won ground.

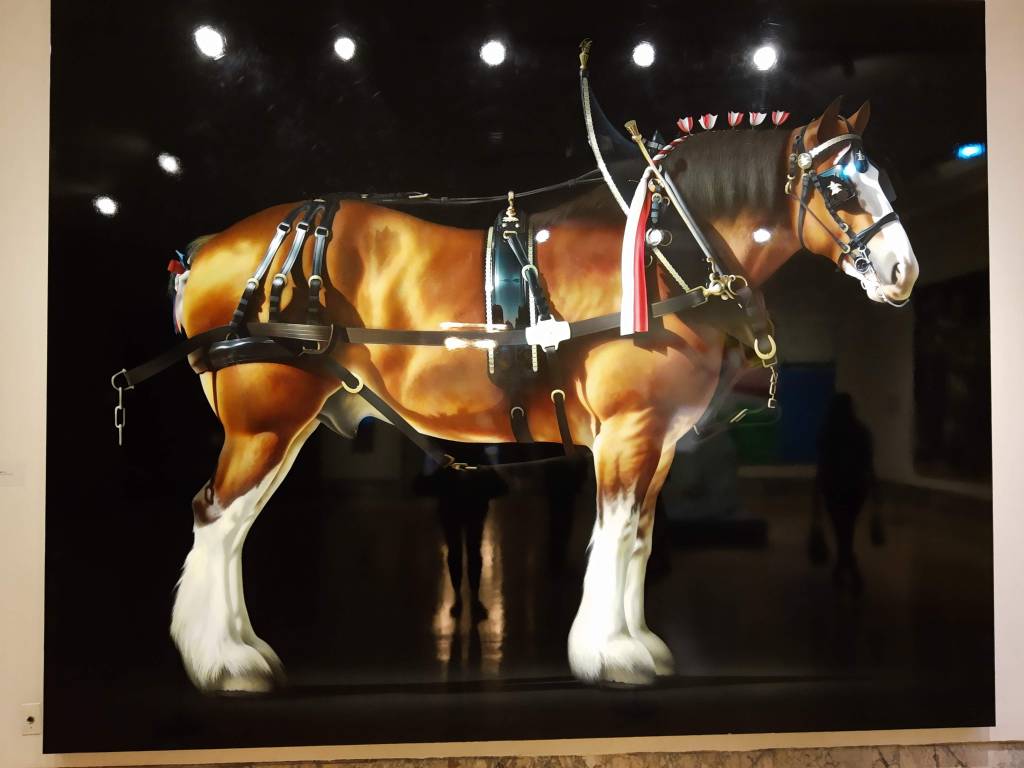

Also, in partnership with the YSU Art Department, the vibrant 150-foot Andrews Avenue Memory Mural along a retaining wall of a historically important corridor has just been completed. We solicited memories from the local community, and students incorporated images and pieces of those, and their own, memories. Memory is important and complicated in a place like Youngstown, a city that has suffered so much loss and is struggling to conceptualize an identity. I think it’s especially important us to offer this younger generation the opportunity to imagine a city they can believe in.

Miltner: Who are some of the writers you’ve brought in for your literary community?

Schubert: So many! We’ve had the privilege of hosting wildly accomplished writers including Philip Metres, Nin Andrews, Philip Memmer, James Arthur, Cody Walker, Kevin Haworth, Jan Beatty, and many faculty of the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts. We’ve also mixed it up with student essayists; storytellers; an international poetry night featuring poems in the original language and the translation; and a humor night one April 1. One December evening Mike Geither read his play Heirloom; it was so moving I found it emotionally difficult to come back to the mic to close the evening. In 2019, we partnered with the Public Library of Youngstown & Mahoning County on an NEA Big Read grant and selected Into the Beautiful North. There were dozens of related events throughout the city for a month, like a mini film festival, immigrant narratives night, and ethnic foods potluck. Luis Alberto Urrea flew in to talk about the inspiration for the individual characters in his book.

Miltner: In a community that is economically challenged, how do you develop funding? And who in the community, or local institutions, or from the state level, contributes?

Schubert: Our community has been incredibly supportive, as have the foundations. We have built up a funding structure that is a mix of support from community members, benefactors, local foundations and state agencies. Our yearly fundraiser is a raffle for a large work of art, typically a birdbath by a local steel sculptor. In all, we have received nearly $200,000 in grants from the Ohio Arts Council, Ohio Humanities, and local foundations.

Miltner: What recent programming has been successful in your literary community?

Schubert: This year’s Fall Literary Festival was successful in the quality of presenters, and the engagement of participants. It’s always so great to see local writers talking with other writers, educators, editors and nonprofit administrators, asking questions and learning more about the literary landscape.

Miltner: The 2020 Fall Literary Festival was held as a videoconference. How was it different from an in-person conference?

Schubert: Well, to begin with, we had a virtual cookie table! I made Allison Pitinii Davis’s aunt’s Greek cookie recipe from the Youngstown Cookie Table Book published by Belt Publishing. Featured writer Janet Wong found cookies in the back of her pantry and described their staleness in hilarious detail. Zoom awkwardness aside, people were wanting to feel a sense of connection. I think they did, but one missing thing was conversations that spill into the hallway and coffee shops.

And we were back in person this year and I was surprised how rusty I felt. I made clumsy organizational mistakes. More importantly, I think feeling connected was also very important this year, and even though there were masks and fewer hugs, the comradrie was everywhere. There are many very fine conferences, so I always ask folks why they come to this one. They consistently say it is the connections they make here.

Miltner: How has the festival impacted your community?

Schubert: It’s the only Youngstown conference for adult writers. The English Festival at YSU, for middle and high school students, draws thousands each year, so there is local context for such an event among literary arts enthusiasts. But previously, adults would have to drive to Cleveland, Columbus, or Pittsburgh to attend in person, which we encourage them to do, but it’s also great to have a conference here.

…they come to hear contemporary work, talks on literature and bringing literature into the community for healing and cross-cultural connection.

Another benefit to local writers is meeting and engaging with writers from throughout the U.S. Really feeling part of something bigger. Of course, some of our attendees are not writers, but readers, students, educators, administrators, and they come to hear contemporary work, talks on literature and bringing literature into the community for healing and cross-cultural connection.

Those who attend from a distance appreciate the low cost of the conference, which makes travel and lodging more possible. And we are fortunate that Youngstown State University partners with us, because this allows undergraduate students to attend free, and some faculty members require their students attend. If YSU follows through with their plan to sunset the NEOMFA, leaving only an undergraduate minor in creative writng, I don’t know yet what that will mean for the conference.

Miltner: Would you share a project Lit Youngstown is currently working on?

Schubert: We had cancellations with the lock-down, including Whitman & Brass, an event that pairs staged readings and a brass quartet playing the music of his day. I was hoping to make this into a series, and was thinking next we would pair James Baldwin and Nina Simone. So Whitman & Brass has been rescheduled for March.

During the lock-down, we sent out an extensive survey to our community, and one consistent point of feedback is that some writers are looking for more in-depth continuity. So this month, we kicked off a series of nine monthly daylong Poetry Intensive workshops. In the morning we’ll talk about books, chapbooks, journals, submissions, presses, readings, things like that. Each afternoon, a different poet will come to talk about different aspects of poetry, and we’ll look at participants’ poems through that lens. For example, when you come, Robert, we’ll talk about the music in these drafts. I’m crazy excited.

Miltner: If an anonymous donor gave you a major gift for Lit Youngstown, what is the dream project you’d immediately implement?

The Big Dream is to buy a large building and begin a writing residency.

Schubert: First I would step up the development of our outreach program. We are inspired by the Wick Poetry Center at Kent State and Director David Hassler who has been a great mentor to us. I’d like for us to be doing outreach with immigrants, veterans, retired residents, patients in medical care, and sexual assault survivors. I love Literary Cleveland’s Essential Worker narratives. Our Outreach Coordinator Cassandra Lawton is currently working in the expressive therapy program at Akron Children’s Hospital and will soon begin a study on writing with cancer survivors.

The Big Dream is to buy a large building and begin a writing residency. In Youngstown, many historic buildings are languishing empty and selling for relatively low prices. I love the model of the Vermont Studio Center, putting studios into a former fire station and school, supporting an indie bookstore, creating links between artists-in-residence and the local elementary school and college.

Miltner: What advice would you offer to someone who might want to launch a community literary program in their city?

Schubert: Collaborate on everything. Keep thinking of new people to bring to the table, to help plan and run events, to shine a spotlight on other community work. For example, when I read Mark Winne’s Closing the Food Gap, a book about food policy, I recognized that it had a lot of relevance to what was happening in Youngstown, a citywide food desert. We partnered with a local co-op on our first book group series and, along with many community development partners, we brought Winne here.

I like to see the literary arts, in addition to creative expression, as a means to understand and work toward solving problems. During the lock-down, I was thinking about the kids at home and parents and teachers looking for literacy enrichment. So we wrote grants and purchased over $10,000 worth of wonderful books for nearly 800 children in Head Start. We also purchased high quality books for children in YSU Project Pass, a program that pairs education students with city 3rd graders who would benefit from reading skills support. Each year we send a $100 donation to a literary arts nonprofit we admire, and this year we selected Black Boys Read, a local initiative.

Miltner: You are yourself the author of several chapbooks and a full-length book. How has your being a writer yourself shaped your role in leading Lit Youngstown?

Schubert: As a student, I went to conferences where I met writers like Bruce Bond, Denise Duhamel, Kimberly Johnson, and former NEA director Dana Gioia. I gained much from classes on how to edit, submit work, and shape a manuscript. From classes and conferences, I met writers who are now lifelong friends. Part of my work is trying to recreate those great experiences for those in our literary community.

Miltner: In your poem “Youngstown Considers the Future,” you write, “We are tired of our Titanic metaphors— / can’t decide if we’re patching up the hole, / steering toward warmer waters, or / arranging the deck chairs.” It seems to me that your dual role of writer/director is encapsulated in these lines. From your perspective, what fresh metaphor would you offer instead?

Schubert:. How about the metaphor of a mural: we’ve cut back the vines, purchased more primer than we knew we’d need, and now we’re ready to create a design harvested from memory and shaped by the young. How’s that for what community building looks like?

Learn more about Lit Youngstown and Karen Schubert by following the links.

~~~

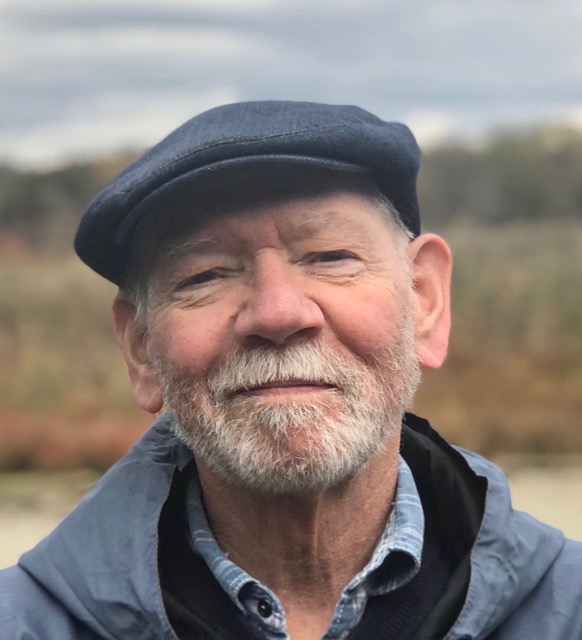

Robert Miltner is a writer, editor, and scholar. His books of poetry include Hotel Utopia, Orpheus & Echo, and Against the Simple, the short story collection And Your Bird Can Sing, and a collection of creative nonfiction, Ohio Apertures. He has received and Ohio Arts Council Award for Poetry, an Ohio Arts Council Writing Fellowship at Vermont Studio Center, and was Poet-in-Residence at the Chautauqua Institution in summer 2021. A professor emeritus from Kent State University Stark and the NEOMFA, and Editor of The Raymond Carver Review, Robert has been a member of AWP since 2012.

~~~

Read my interview with Robert Miltner for Rust Belt Girl here. Like this interview? Comment below or on my FB page. And please share with your friends and social network.

Are you a Rust Belt writer interested in seeing if your own author interview or book review might be right for Rust Belt Girl? Pitch me through this site’s contact function.

Check out my categories above for more interviews, book reviews, literary musings, and writing advice we can all use. Never miss a post when you follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~Rebecca