By Marjorie Maddox

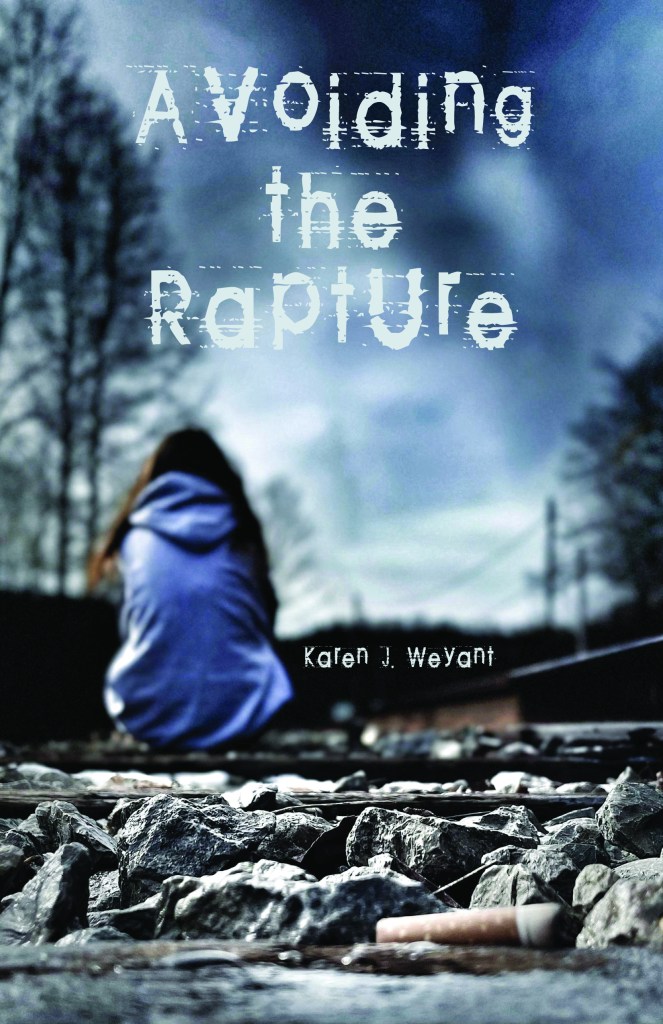

In Karen J. Weyant’s first full-length book of poetry, Avoiding the Rapture, there is no avoiding the evocative and sometimes contradictory landscape and convictions of the Rust Belt. In a town defined by its bars and churches, river and railroad tracks, closed factories and forbidden swimming holes, Weyant gives us both the desire to leave and the need to cleave. No matter our background, she makes this space ours—ownership and rebellion a familiar if not always pleasant home.

We begin with belief so strong it takes hold of a town—“Every girl I knew got religion/at the same time they caught Disco Fever.” Salvation is a type of escape to be embraced or rejected. “Facing uncertain futures,” the poet explains, “we waited to be whisked away in [both kinds of] sparkle.” And yet by “avoiding the rapture,” she counters, “[w]hen everything disappears, everything you see will be yours,” a mixed motivator for a place that when you aren’t reveling in it, you’re scheming a quick departure.

Within this back-and-forth identity quest, the narrator looks for signs and visions in roadkill rising from the dead, in Jesus in dryer steam at the local laundromat, in “one of the Horsemen/in the hind leg of a Holstein cow,” and in “saints/in real estate signs buckling under buckshot.” There are also “man-made miracles” where the narrator “dump[s] grape juice into Gallagher Run,/hoping the muddy swirl would turn into wine,/. . . [or] pretend[s] the stale angel food cake. . . was really manna.”

Woven throughout the book is a sequence that often begins “The Girl Who…” and perceptively defines identity. “The Girl Who Parted Mill Creek with Her Toes” offers nature as one way to “ignore the grown-up talk/of factory closings, lost jobs, and foreclosures.” This path also allows for leaving the church while retaining its lore and, at times, alure. For example, the post-industrial mass exodus of families is linked to the narrator’s Exodus-like parting of the creek with her toes. Likewise, in another poem, an abandoned and deteriorating church evolves into a new type of sanctuary.

Throughout, insects swarm, dazzle, or sting. There is “the drone/of factories in a metallic round of cricket song” and “june bugs hurling against back doors.” Not unlike the town’s inhabitants, in “To the Girl Who Talked to Summer Insects” “[s]ome insects were silent, others angry or lost.” Elsewhere, mayflies—“ghost stories [come] alive”—become reminders “we lived among the dead.” The plague-like buzzing of blackflies usher in arguments over money and heat. “June/ [is] heavy with horseflies. . . .cicada shells. . .cracked under our feet.” In dreams, butterflies get “caught in backyard grills”; in real life yellowjackets die in/escape from a flaming nest; the narrator rescues grasshoppers from a ball of ice. Eventually, end-of-the-world prophesies drown out miracles.

In this way, even the word “miracles” begins to lose its mystery. In family life, the word becomes synonymous with describing impossible situations: a truck that “would need a miracle to get through the summer,” a sister who “would need a miracle to get through high school,” and a father who “would need/a miracle to get a job at his age.”

As tensions increase in the run-down town, so does the narrator’s desire for flight. “[W]e planned our new world. . . . we knew we had to leave,” she recalls. The coming-of-age departures are small and large: heels, makeup, drinking, boyfriends with the nicknames of beers, the recognition that, on many levels, “every ripple has danger” and that [r]eal girls learn to toughen/the soles of their feet. . . .Accept . . .fate.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that there aren’t moments of daring and flight. Through sheer determination, the narrator “[spins] in the August heat until [she] could fly.” Bravely, she catches bees or reaches out to touch a two-headed calf. We watch as her father helps her bury a dead bird. Always drawn to water, she listens to rivers talk and “sw[ims] late at night/in the gravel pit pond.” She counsels, “Follow the fireflies.”

In these ways and others, Avoiding the Rapture whoops and hollers with independence and survival. It is a stirring, well-crafted ode to place, where “girls still ride the beds of pickup trucks . . . .[and] learn how to catch maple seeds/in their teeth, and how to spit them out.” It is a depiction of individuals who, even if they don’t learn to fly, learn to balance while wind “comb[s] through their long hair.”

Here’s to the young women of the Rust Belt, fiercely and perceptively portrayed in Karen J. Weyant’s new collection, Avoiding the Rapture.

Karen J. Weyant‘s poems and essays have been published in Chautauqua, Crab Creek Review, Crab Orchard Review, Cream City Review, Fourth River, Lake Effect, Rattle, River Styx, Slipstream, and Whiskey Island. The author of two poetry chapbooks, her first full-length collection is Avoiding the Rapture. She is an Associate Professor of English at Jamestown Community College in Jamestown, New York. She lives, reads, and writes in Warren, Pennsylvania.

Professor of English at the Lock Haven campus of Commonwealth University, Marjorie Maddox has published 14 collections of poetry—including Transplant, Transport, Transubstantiation (Yellowglen Prize); Begin with a Question (International Book and Illumination Book Award Winners); and the Shanti Arts ekphrastic collaborations Heart Speaks, Is Spoken For (with photographer Karen Elias) and In the Museum of My Daughter’s Mind, a collaboration with her artist daughter, Anna Lee Hafer (www.hafer.work) and others. How Can I Look It Up When I Don’t Know How It’s Spelled? Spelling Mnemonics and Grammar Tricks (Kelsay) and Seeing Things (Wildhouse) are forthcoming in 2024. In addition, she has published the story collection What She Was Saying (Fomite) and 4 children’s and YA books. With Jerry Wemple, she is co-editor of Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania and the forthcoming Keystone: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania (PSU Press) and is assistant editor of Presence. She hosts Poetry Moment at WPSU. See www.marjoriemaddox.com

Rebecca here, with many thanks to Marjorie for this beautiful review of Karen’s poetry collection. I can’t wait to dig in! What are you reading and writing this month, as we start working our way through the new year? Let’s discuss in the comments.

Are you a Rust Belt poet or writer? Do you write book reviews–or conduct interviews of Rust Belt authors? If so, think of Rust Belt Girl for a guest post, like this one. And check out the handy categories above for more writing from rusty places.

Find me on FB and on IG, Twitter, and Bluesky @MoonRuark

And follow me here. Thanks!