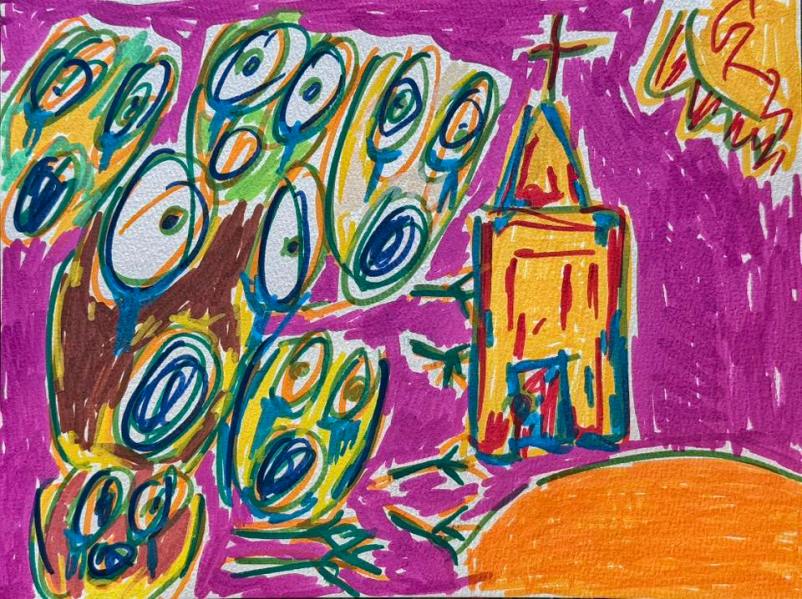

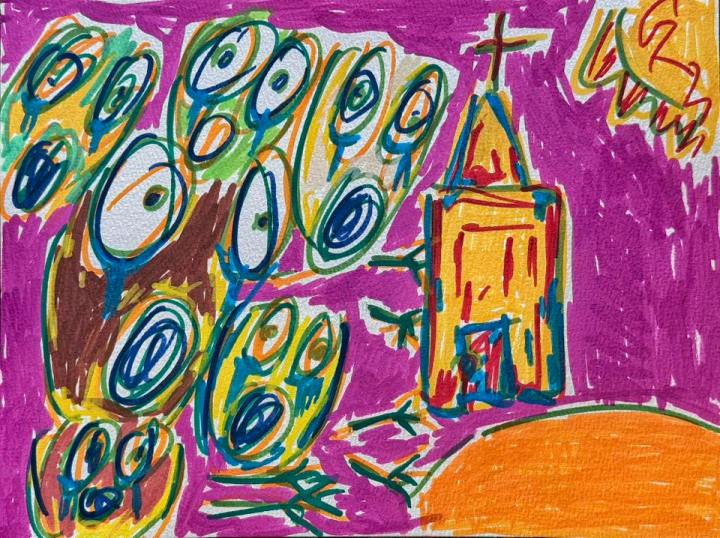

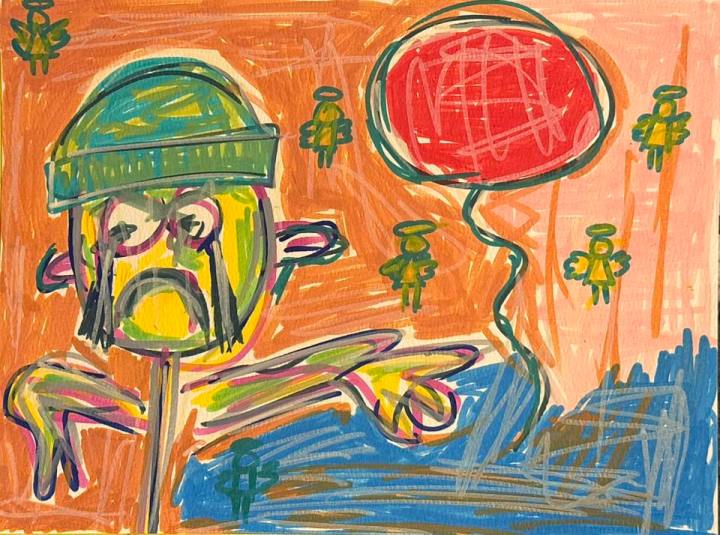

Poet, photographer, and model literary citizen, Justin Hamm inspires with his offering–the third installment of a series of guest posts here at Rust Belt Girl. Thank you, Justin! His essay about speaking in tongues feels especially personal, presented as it is from a child’s perspective. It feels “close” to me, in more than one way. Justin’s essay is accompanied by his original folk art, and I have to say, I didn’t see this coming. But I absolutely love it. Here at Rust Belt Girl, we know the American Midwest is vast and multitudinous, and so are its people, their inspirations, their stories, and their art.

Because Justin is truly “Midwest Nice” and humble, he might not brag to you about his TEDxOshKosh Talk, “The American Midwest: A Story in Poems & Photographs, but I’ll do it for him. This is a good place to start, if you’re new to Justin. In his talk, he asks some of the same questions we’ve been asking at Rust Belt Girl all these years. A big one: Is “flyover country” an appropriate term for the Midwest? Justin explores that vital question through inspection of the overlooked or the avoided, including rust (holla!), thunderstorms, everyday people doing everyday things, politics, social class, and more. It’s well worth a watch-and-listen.

But first. Let’s read and discuss Justin Hamm’s…

The Wind With a Secret Shape

I was eight maybe nine years old Wednesday nights my grandparents used to

take me to a small Pentecostal church that sat on a grassy rise just outside of

town it had once felt isolated tucked out in the quiet but the town had crept

outward now it sat beside a gas station a lumberyard and a row of fast-food

joints the holy and the ordinary rubbing shoulders the church rectangular part

brick part white siding a white cross stretching off the roofline like an arrow

pointing to the shifting Illinois sky inside the pews angled toward a low

platform where the preacher shouted and a four-piece band laid down rhythm

the cushions a deep royal blue clean saturated almost regal I remember that

color better than my childhood bedroom the building always felt old but never

run-down the women cleaned it like a calling while the men kept it maintained

it smelled of floor polish and breath mints old hymnals and hairspray a past

preserved a place where time seemed fixed in place

I wanted to be a good boy I tried to follow the sermons caught a phrase here or

there but mostly folded handouts into paper planes or built hymnbook

pyramids sometimes I curled up on the back pew and drifted off lulled by the

rhythm of scripture and song until the spirit moved when it hit the preacher

everything changed he’d leap down the steps whirling stomping at the devil

howling Jesus’ name until his face went red and purple sweat soaking his brow

and then the tongues came strange breathless syllables rolling out like a chant

that bypassed the brain entirely the holy ghost made you do things that was

just how it worked I accepted it the way you’d accept sunrise or gravity

and I believed too believed fully if somebody said the spirit is with us tonight

I’d scan the sanctuary up in the corners where wall met ceiling under pews

between swaying bodies I didn’t expect to see it exactly but I wanted to know

where it was it filled me with something like fear but not only fear there was

longing in it too hunger a sense that something just out of reach might solve

everything the holy ghost like a wind with a secret shape a bird made of breath

maybe God’s own breath moving invisibly through the room I believed it

entered through the mouth that explained what came out the old men would

rise in their too-large suits limping loops around the sanctuary hands raised

speaking in tongues the women would fall stiff to the ground eyes rolled back

mouths twitching that’s how I knew the ghost was on the move I tracked it

sinner to sinner and sometimes it came close the person next to me would

sway eyelids flickering syllables rising up like springwater through stone my

chest would lift my legs would buzz my mouth would soften and open almost

involuntarily I’d think this is it just let yourself go let it take you I opened my

mouth and nothing came I tried again wider harder I prayed the best I knew

how I swallowed the air like it might carry something eternal and then I waited

Justin Hamm is the author of five poetry collections, including O Death (2024), Drinking Guinness With the Dead (2022), and The Inheritance (2019), as well as a book of photography, Midwestern. He is the founding editor of the museum of americana and the creator of Poet Baseball Cards.

Like this post? Like this series? Let’s discuss! Comment below or on my FB page. And please share with your friends and social network.

Are you a Rust Belt writer interested in seeing if your own post, or author interview, or book review might be right for Rust Belt Girl? Hit me up through this site’s contact function.

Check out my categories above for more guest posts, interviews, book reviews, literary musings, and writing advice we all cab use. Never miss a post when you follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~Rebecca