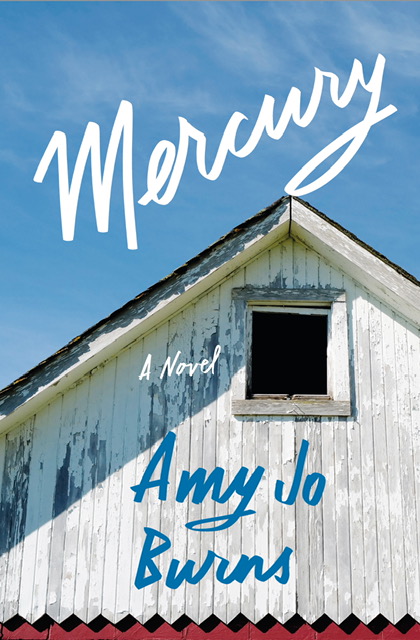

Let’s begin with a sample paragraph from Amy Jo’s stunning literary (also mystery) family saga:

Spring was breaking through in lilac buds and daffodil shoots, but winter held on. Tufts of dirty snow clung to curbs, and porch steps, and parking lots. The heat had stopped working in the Citation, and Marley shivered. Theo was bundled in the backseat; she caught a glimpse of him in the rearview mirror. Then her eye snagged something else behind her–someone limping from a snowbank into the intersection. Marley slowed to a stop and turned around.

Whew. Good stuff.

Amy Jo, your main character in this Western-PA-set novel is Marley, whom we first meet when she’s 17. You left your Western-PA hometown for college around that age. What was it like to write this book and “inhabit” Marley’s character in a place (and time) similar to the one you were raised in? And how similar is your real-life family to Marley’s found family?

Marley is a really special character to me. When I was creating her, I took the qualities I love most about my best friends from home and put them into her character. Her willingness to step into someone else’s messiness, her ability to tell the truth in such a loving way, and her desire to build a business with her own creative stamp on it are all qualities I really admire about my oldest friends. Marley showcases what I think real resilience actually looks like. It isn’t perfection or misery or loneliness—it just comes through in a big-hearted, flawed human who shows up for the people in her life.

The Joseph family in the novel is like mine in that we’re both a family of roofers—which means both houses were full of grand storytellers, brave hearts, and lots of tar-stained jeans. The house I imagined the Josephs living in was inspired by the old Victorian house my grandparents used to own in my hometown. I’d always loved that house and couldn’t imagine any other place a family of roofers would live. The characters in Mercury come from my imagination, but the bond they feel with each other—the sometimes too-close intimacy they have with one another is absolutely something any member of my extended family can relate to. When it comes down to it, I’d say both families care about the same thing—keeping people safe under roofs and on top of them.

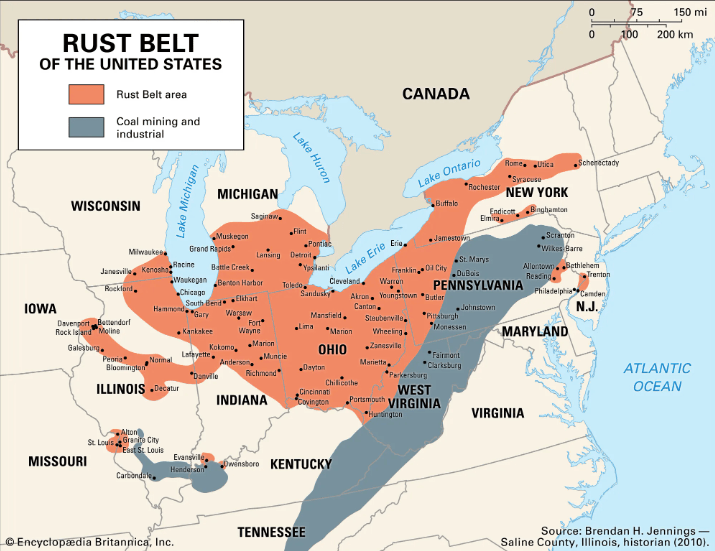

This novel is mostly set in the fictionalized town of Mercury. How did you go about constructing this place, this “forgotten Rust Belt town.” Did you use Pinterest boards or clip photos from magazines? Was there map-making involved to mark where the salon, post office, and library stand? And, as the daughter of real-life roofers, do you picture this town from an aerial/rooftop view?

Mercury is heavily inspired by my own hometown, which I also wrote about in my memoir Cinderland. When I started writing the early pages of this book, I knew it had to be set in Mercury—a place I know, love, and left. So most of the early “research” came from my own memory, and then I squared it with pictures from the 1990s and also by talking with my parents. My dad drew a map of the church steeple and attic (which both play an important role in the story), and I talked with my mom about what it was like to help build a roofing business from an administrative perspective. It was really special to get to share a bit of this project with them, especially since so much of the book is about what it means to belong and how we claim home for ourselves.

I hadn’t imagined my hometown from any aerial views until I started putting characters on roofs pretty early in the process of drafting the book, and it was the coolest thing to envision this place anew from an entirely fresh perspective. I was able to find a few aerial videos of my hometown to watch, which really helped me fill in the landscape for what these characters find when they’re up higher than everyone else.

I’d call this book a literary family saga; however, there is also a lot of romance—some steamy! What’s your best tip for writing romance or sex that deepens character and moves plot?

I would say my best tip is that sex is never just sex. Falling in love is one of the most monumental things we experience as humans—it shows us at our best and our worst—and I think it’s really important to reflect it in literature. When I’m writing romantic scenes, I’m always considering what each character is risking about themselves in a very unique way—are they sharing something no one else knows? Are they saying one thing and thinking another? What is it about falling in (or out of) love that changes how they see themselves? What past events have shaped how a person approaches their most intimate moments? Those scenes are such a great way to show what a character deeply wants and what they fear, whether they’re aware of it or not. And when all that juicy backstory collides with someone else who is just as complicated—it’s fictional gold!

Like in your last (gorgeous) novel, Shiner, you explore profound female friendships in Mercury. Can you talk about how you developed the friendship on the page between Marley and Jade? When you’re writing, do you do character studies/background/backstory with detailed info–any that doesn’t make it into the book?

Mostly what I do when I’m building relationships between characters is think about it A LOT. I write many drafts over a long period of time and throw out a lot of material, usually because that’s how I’m getting to know the characters. Scenes will start off as sketches and they get more detailed as I learn who the characters are. Many of the scenes between Jade and Marley felt very cliché for a long time as I was working, and I’d have to go back in and re-work them to go deeper so they felt earned and true.

I am such an impatient person (what a terrible trait for a writer!), so character studies always feel like they’re detracting from the real heat of the story I’m working on. The only thing I usually do outside of drafting itself is create a playlist for each book that I write, and I’ll include songs for each of the characters. It helps me track down their psyches, their moods, their secrets. You can learn a lot about a person if you know what songs they’re listening to when they’re alone.

In this novel you touch on dementia. What kind of research was involved there? As this book is set in the 90s mostly, was there any other, historical research you had to conduct for verisimilitude?

I had a family member with a form of dementia (though under different circumstances than those in the book), so I used that as the basis for building it in the novel. I decided not to do much clinical research on it because I wanted to portray it through the eyes of a family who isn’t sure what is going on. So often we don’t get the answers we are looking for in real life when it comes to medical diagnoses, and it was really important to me to give that truth a lot of space in the novel.

Motherhood is portrayed in a very real, and sometimes heartbreaking, way in this novel. Marley’s mother-in-law says, “This life is unmerciful to mothers.” You’ve got two young children at home. How has your writing practice (and product) changed since becoming a mom? And, follow-up, what is your favorite novel for exploring themes of motherhood?

The biggest difference in my writing practice is that I have to keep my working hours to match my kids’ schedule. It is GIGANTICALLY easier now that they’re both in school, though I rarely get done what I’d like to in the course of a day. I remember when my son was an infant and my writing sessions were so short, I thought I’d never finish the book I was working on, which turned out to be Shiner. Sometimes my writing sessions would only produce a few hundred words. I had to learn to talk myself through it and say, “Maybe no one will ever see it, but I’d still like to try.” And I’d repeat that to myself over and over when my daily frustrations came. And the book got done!

In terms of my favorite book about motherhood, I once attended a talk by Nicole Krauss just after she’d published Great House. Someone in the audience asked her how she was able to write and be a mother, and she said, “I wouldn’t have been able to write this book if I hadn’t become a mother.” It was so encouraging to me, as I was contemplating how I might have kids and continue to write. That story inspires me still.

A lot of the plot of Mercury centers around the family’s church—but not necessarily around worship. No spoilers, but can you talk about how religion, faith, and or belief works in the world of this novel—and maybe also in your own life?

My faith is a huge part of my life and my creative process. I think maybe writing books is a form of prayer for me. What I love about it is that the page becomes a place for my uncensored thoughts, my questions, my frustrations, and—most powerfully—the things that I love and I think are worth fighting for. It feels like a quiet place where I can meet God without judgment, where I don’t have to be any other version of myself but the real one. Also, I do a lot of listening when I’m writing which feels very peaceful.

In this particular story, many of the characters have an idea of what “religion” is, but what they’re all hungry for is faith. Faith in a God who loves them just as they are, and faith in each other. I like to think each of them encounters God in an unexpectedly meaningful way in the book, and usually it’s through they way they learn to love each other.

For those of us who aren’t just readers but who are also writers, what’s your favorite generative prompt for a writing day when the words just aren’t coming?

I absolutely recommend starting with a memory from childhood you can’t get out of your head. Try retelling it to yourself from an adult perspective (which you can interpret any way you like). I actually began Mercury in just this way—the opening scene of the book is a memory of mine from a little league game when I was around nine years old. This exercise was how Waylon’s character first came to life.

Tell us how the reaction to Mercury has been on your visits to libraries, bookstores, etc.?

It’s been really wonderful. When Shiner came out in spring of 2020, there were no stores open, so getting to visit libraries and bookstores has been the best thing about publishing Mercury. My favorite thing is hearing about readers’ favorite characters and how they saw themselves in the story. I love it when that happens in a book I’m reading, so getting to provide that experience for fellow readers is a real gift.

What are you writing and reading right now? And what are your kids’ favorite children’s books, lately?

I love this question! This year I’ve been trying to take my time and read longer books (which I’m calling “biggies”), so right now I’m reading two—Iron Flame by Rebecca Yarros and East of Eden by John Steinbeck. I’m really enjoying them both. Right now my son, who is nine, is loving the entire Percy Jackson universe by Rick Riordan, and my six-year-old daughter is very into Dog Man by Dav Pilkey and the Max Meow series by John Gallagher. I love seeing them read!

Writing-wise, right now I’m working on a novel about the true story behind a famous country-folk singer’s disappearance. I don’t know if it will be my next book or not, but I’m really enjoying the work itself. Thank you so much, Rebecca!

Amy Jo Burns is the author of the memoir Cinderland and the novel Shiner, which was a Barnes & Noble Discover Pick, NPR Best Book of the year, and “told in language as incandescent as smoldering coal,” according to The New York Times. Her latest novel, Mercury, is a Barnes & Noble Book Club Pick, a Book of the Month Pick, a People Magazine Book of the Week, and an Editor’s Choice selection in The New York Times. Amy Jo’s writing has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Elle, Good Housekeeping, and the anthology Not That Bad.

You can find her on Instagram at @burnsamyjo.

Many thanks to Amy Jo Burns for sharing her insights and time–and kid book recs– with us here at Rust Belt Girl. I know I can’t wait to read what’s next from Amy Jo!

Like this interview? Comment below or on my fb page. And please share with your friends and social network. Want more? Follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~ Rebecca

*Photos provided by Amy Jo Burns